By the close of the 19th century, the growing tendrils of industrial travel had transformed Europe’s provincial backwaters into profitable centres of tourism. The Alps, once spurned as a region of backwardness and superstition, now attracted thousands seeking their own heart-quickening encounters with the Sublime. The picturesque town of Aarmühle, pinned between Lakes Brienz and Thun in the imposing shadow of the Bernese Oberland, was perfectly situated for this new breed of Romantic traveller. Since the early 1800s, steamships had plied the opalescent waters of Lake Thun bearing crowds of bourgeois sightseers from the increasingly urbanized Swiss Plateau. The Victoria-Jungfrau welcomed them, a luxury hotel overlooking the green meadows of the Hohematte park and the drama of the mountains beyond.

Yet Aarmühle, exposed to this new cosmopolitan clientele, was ashamed of its rustic roots. A rebrand was proposed by local councillors, and in 1891 the artless name (‘Mill on the River Aare’) was shed along with any trace of the town’s peasant past. An altogether new and fashionably-hydrotherapeutic title was formally adopted – Interlaken.

Over the subsequent century and a quarter, Interlaken has had to adapt to the changing face of tourism. When we arrived on a muggy July afternoon we found the town’s former promise of luxury had been replaced with a promise of ‘adventure’. The Victoria-Jungfrau remained, it’s prices eyewatering as ever, but the Hohematte was no longer a parading ground for the wealthy, rather a landing pad for an incessant spiral of parachutists tumbling from helicopters far above the valley floor.

Our shabby backpackers hostel was embedded in the wing of a former art deco resort that, at least from the outside, maintained the grandiosity favoured by the 19th-century hotelier. Early reviews of the Mattenhof Resort are cautiously positive, though never glowing. It appears to have serviced the lower-tier of bourgeois traveller, those who could only dream of the Victoria-Jungfrau, yet nevertheless expected its imitation. Chateau-like in design and replete with extensive gardens and shadowy interiors, the building felt historical, if a little too authentically so. The inner flesh was tired and lacklustre; the corridors unlighted; the walls chipped; the faded carpet threaded and snagged. Reception was run by a friendly-enough balding man in shorts and flip-flops who spent his shifts vaping on the front porch. He brusquely directed us to our room in the east wing where, upon arrival, we found a family of flies already in residence.

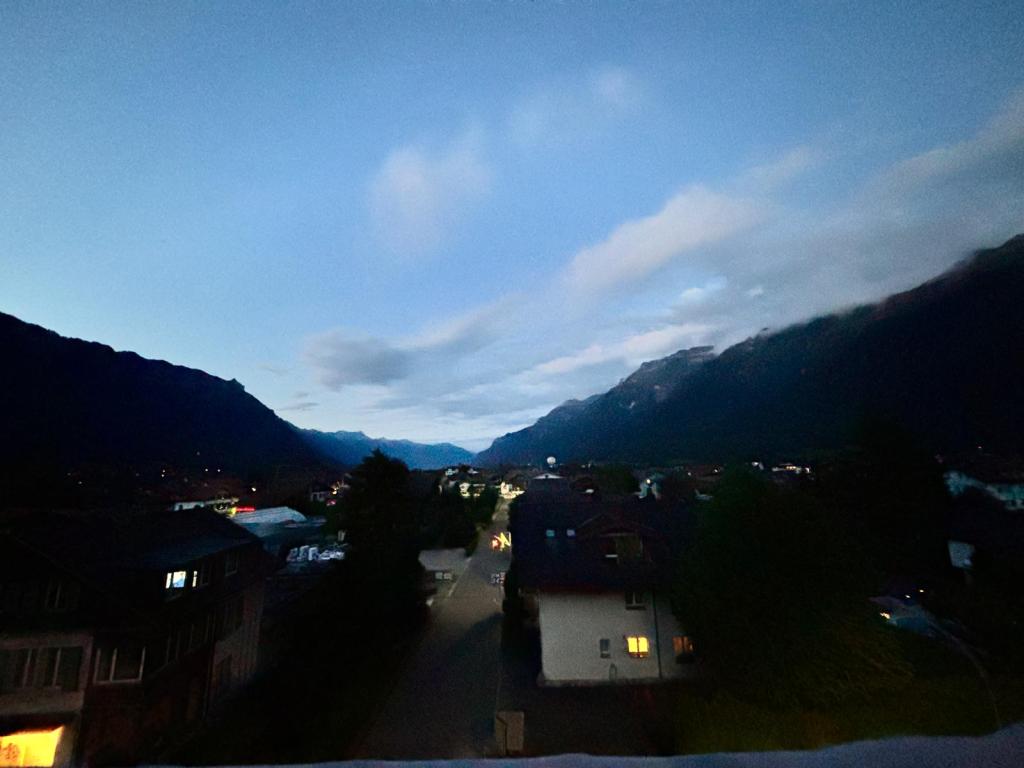

Our scant room was redeemed by one addition – a ramshackle wooden balcony furnished with two plastic chairs looking out across the valley. Three stories below, the local ‘nightclub’ – more a meagre bar – entertained the same rasping locals each night. But they didn’t bother us. Our balcony was a refuge from the cheerlessness of the room, the safety we returned to each evening to watch dusk fall, the place we sought each morning, coffee in hand, to witness the day begin anew.

South of Interlaken, the forested foothills part to reveal the deathly pale face of the Jungfrau. Into this cleft a train runs, parallel to the silty churn of the Lütschine that barrels down from its glacial origins towards Lake Brienz. We alighted early at Wilderswil on a misty and ominous morning to find the carriage desolate. At Zweilütschinen the line forked in accord with a split in the river; we angled south towards the town of Lauterbrunnen, buried in a trench-like valley, where the rack railroad lurched into gear and the ascent began. Across the trench, the Staubachfalls slid soundlessly over the pale rockface. The reclusive town of Mürren, accessible only by cable car, perched atop the cliffs like a watchful cat.

Zigzagging up the escarpment, we watched grey forests give way to silver meadows. Our terminus was Kleine Scheidegg, a mountain pass beneath the iconic triumvirate of the Oberland: Eiger, Mönch, and Jungfrau. The names of these iconic mountains are rooted in legend. Eiger (Ogre) is the man-eater – its black north face (Nordwand), having claimed the lives of at least 64 climbers, has earned the nickname Mordwand (‘Murder wall’). According to legend, the Eiger longs to lay its hands on the pure white snows of the Jungfrau (‘Maiden’ or ‘Virgin’). Only the venerable Mönch (Monk) stands between them, guarding for all of eternity.

As we pulled into Kleine Scheidegg, the three were shrouded in an eery silence. The startled server of the station café poured us some bracing coffees, and we stood out in the grey stillness, bewitched by the enormity of our surroundings. We had fifteen minutes before the Jungfraubahn would tunnel us into the bowels of the Eiger to ascend through darkness to Jungfraujoch, the snowy saddle between the summits of Jungfrau and Mönch. I could just make out our destination, the so-called ‘Top of Europe’, a smudge of human endeavour against the blinding skyline. It was hard not to feel the surrounding behemoths of rock and snow were not lifeless, that some unspeakable threat slumbered up there in the frozen altitude.

The final leg of our journey bore us into the very innards of the mountains. The ascent through impenetrable darkness was broken up by a ten minute interlude to acclimatize us to the heady altitudes, but this did little to alleviate the nausea we felt as we pulled into the cold, cavernous station. After a breathless fifteen minutes spent in a state of semi-panic, we wandered drunkenly into the freezing labyrinth, musing disinterestedly at an array of ice sculptures as we sought out the lift that would carry us to the bracing air and unbounded views of the joch. When we finally tramped onto the snowy shoulder, we felt no less dwarfed by the landscape than we had at Kleine Scheidegg far below. To the north the Oberland dropped in ridges and folds towards the foggy flats of the Swiss Plateau, while south the spectacular Aletsch glacier poured away to a canvas of snowy peaks, steely blue beneath the heavy sky.

After a bitterly cold inspection of the panorama, we slithered back into the relative warmth of the indoors. The standard commodities of any Swiss tourist attraction awaited us – excessively priced watches and a glittering array of Lindt chocolate. As ever denser crowds thronged in with each successive arrival of the Jungfraubahn, we found ourselves caught up in a consumerist frenzy. The timepieces we could ignore, but we plundered the chests of chocolatey treasures, elbowing grown adults aside until our pick n’ mix boxes were brimming.

With one last cursory glance at the vista, chocolates swinging merrily in hand, we reboarded the train for the viewless return leg back to more sensible elevations. With no unbelievable landscape to engross us, our blank gazes fell upon the TV screen directly ahead. A corporate showreel featuring a panoply of celebrities and multinationals provided the illusion of entertainment. There was a video of Roger Federer playing tennis on the joch, followed by a video of the Swiss football team playing football on the joch, followed by a video of a Swiss singer singing Swiss songs on the joch. Cameos followed cameos, sponsorships followed sponsorships. Numbly shovelling down Lindt well past the point of pleasure, I felt my spirits lapse helplessly into a dreadful cynicism. Had the whole experience ever been about nature’s transcendent vastitude? Or was it always just another offering at the alters of consumerism?

Thirty men died in the construction of the Jungfrau railway. There is a memorial to them at the ‘Top of Europe’, a wall of mostly Italian names easily bypassed en route to chocolate and views. As we trundled back to Interlaken, I wondered whether this stubborn feat of human engineering was really worth the human cost. The outright pessimist in me went further: was it not disingenuous, even morally wrong, to have stood upon those high snowfields without ever having sweated to get there, especially when it had taken death to get us there?

For all the spectacle of the Jungfraujoch, my prevailing memory of awe in Interlaken came from our unassuming hotel balcony. There we sat that evening, cups of tea warming our hands, watching a stormy dusk unfurl across the valley. The bone face of the Jungfrau turned ashen under the navy clouds, and a groan of thunder sent shivers along the forested slopes. As lightening flashed above the furrowed clouds, the gothic gloom of the Alps lulled me into a state of wonder at their callous, unfathomable power.

Our efforts at making remote places accessible, at condensing the awe-inspiring onto a postcard, risks displacing the wonder that draws us there in the first place. The Jungfrau and her po-faced neighbours may be spectacular, but there is something equally unsettling about them. From the safety of our balcony, our shabby insect-riddled room glowing cosily behind us, I imagined myself up there on the joch with night pouring in. I imagined the utter desolation of being stranded in true wilderness; the panic of plummeting temperatures; the terror of entrapment; the certainty of an unforgiving, lonely death. And I realised that luxury means nothing more than the most basic warmth and safety against the seismic terrors of the world.

As the feeble lights of Interlaken struggled against the oily night, I found myself struck more by the frailty of humanity than by its strength. The engineering efforts of men long dead, who had afforded me a chance to eat chocolate closer to the sky, could not eliminate the antisocial evil of the mountains they had seemingly conquered. Beneath the golden smile of tourism lurks something eternally sinister; something that, as I looked out onto those black slopes, seemed to leer back, whispering its demonic presence. With a tremble I turned inside, glad of my springy mattress and my creaky bedframe, glad for that tired room I could call a home for those brief few days we spent in Interlaken.

Leave a comment