As he gazed across that milky vista of saw-toothed peaks and formidable massifs, Edward Whymper must have felt unstoppable. It had been four years since he first laid eyes on that spectacular mountain, and now, perched upon its precarious summit, the fickle alpine weather was rewarding him with a panorama of unexpected clarity. Before him lay a pantheon of giants, from the nearby Weisshorn and Monte Rosa, to the northern summits of the Bernese Oberland and the distant bulk of Mont Blanc. Each peak had its own tales of struggle, ambition and tragedy in that decade now called the Golden Age of Alpinism. But the razored-edge spine upon which Whymper stood was his own personal tour-de-force. After seven fruitless, frustrating attempts, the Matterhorn was finally his.

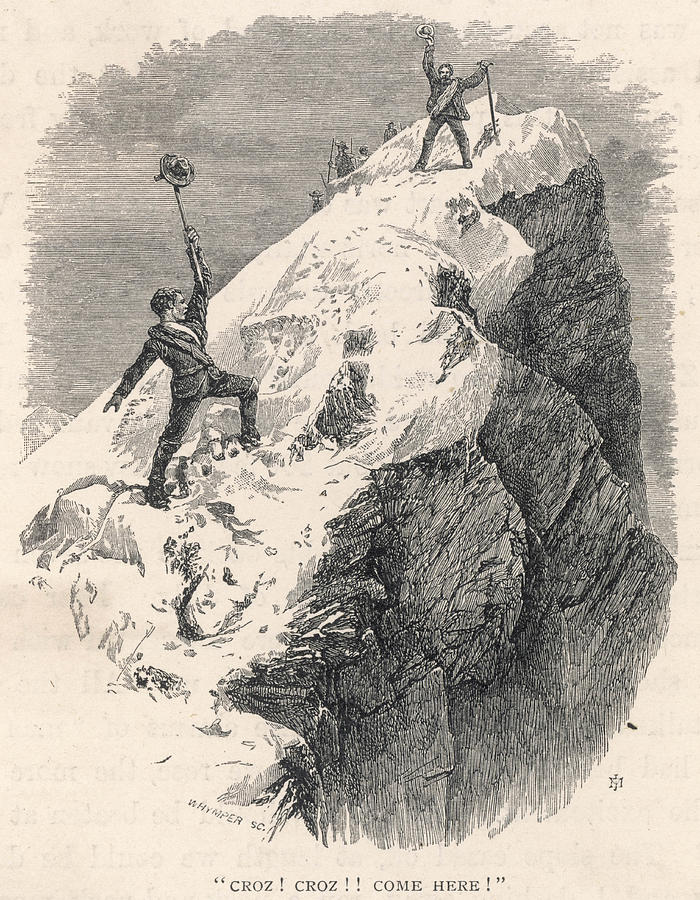

Along with his team of English adventurers and native guides, Whymper passed an easy hour in the dazzling sunlight. Strangers only days before, the men had rallied for a swift attack on the Hörnli Ridge after news reached Zermatt of an Italian expedition making an attempt from the south-west. The Rev. Charles Hudson, known for the first ascent of the Dufourspitze, matched Whymper in experience and skill. There was Lord Francis Douglas, a teenage aristocrat with more years training than his age would suggest, and Douglas Hadow, a protégé of Hudson completing his first season in the Alps. Michel Croz of Chamonix and Peter Taugwalder of Zermatt brought local knowledge, and two of Taugwalder’s sons provided youthful brawn – though only one would go on to make the full ascent.

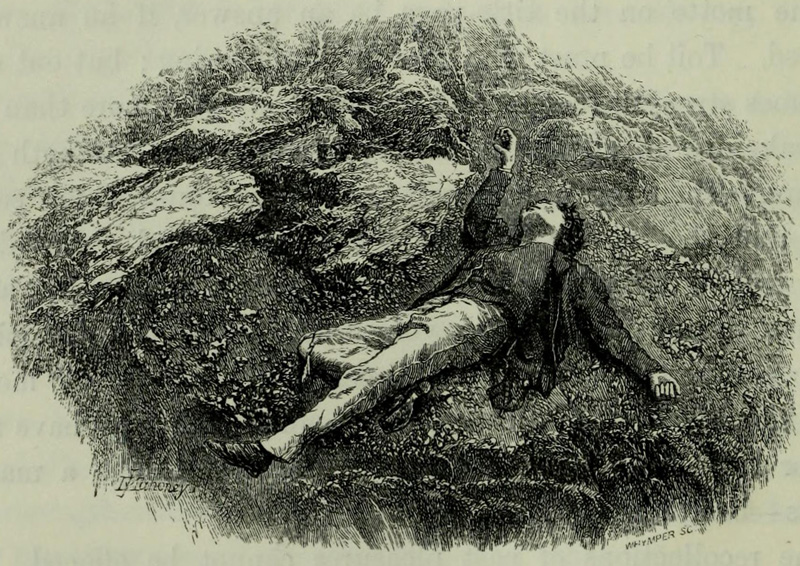

As the team now braced for its hazardous descent, Whymper lingered, making a hasty sketch of the summit. Croz moved off first, guiding the inexperienced Hadow step by step, with Lord Douglas and Hudson following close behind. On less vertical gradients the men would have kept about twelve feet apart, ensuring the rope that connected them remained taut. But this was far from practical on such a precipitous descent. It was Hadow, shimmying gingerly down the rockface, who invited catastrophe with the smallest of mistakes. A slip sent him crashing into the back of Michel Croz, who was thrust unwittingly towards the abyss. The rope jerked violently, and one by one, before any had time to react, Hadow, Hudson and Lord Douglas were hauled explosively forward. Only Taugwalder Sr., further back, had time to secure himself against a nearby rock. But the pressure was too extreme. The rope snapped, leaving Whymper and the two Taugwalders alone and horror-stricken as their companions disappeared over the mountain’s perpendicular edge.

Three bodies were recovered from the glacier four thousand feet below. Lord Douglas’ was never found. An inquest found the rope to be a frayed reserve which no experienced mountaineer would ever have used except in an emergency. Though the trial saw no evidence of foul play, Whymper’s account of the ascent, Scrambles Amongst the Alps, painted Taugwalder and his son in an unfavourable light. The Swiss guide was ostracised from the mountaineering community, and with his professional reputation irrevocably damaged, he led an isolated existence until his death over twenty years later.

The extraordinary story of that first ascent is befitting for a mountain as spectacular as the Matterhorn. No desktop wallpaper or Toblerone tube can prepare the eye for its immensity. Its quirky conicity – like a crooked wizard’s hat – is curbed only by the menacing blade of the Hörnli Ridge. Sunlight thrown upon either face creates an improbably stark contrast, transforming the mountain into a triangular yin-yang. And because the Matter valley is little more than a crevice sliced through great towers of rock, when the sun drops behind the heights and Zermatt sinks into twilight, the Matterhorn glows on like a preposterously-sized lava lamp.

Zermatt has changed since Whymper stood outside the Monte Rosa hotel contemplating that remarkable mountain. Back then the town was an isolated cul-de-sac at the bottom of Switzerland, but today, despite only marginal gains in accessibility (one trainline, a prohibition on cars), it is a tourism hub the year round. The pristine streets are squeezed with hiking stores, ski-rentals and chocolatiers; tourists grossly outnumber permanent residents; and infrastructure permits access to heights once reserved only for the bold.

On a clear July morning, the summer heat building towards its midday apex, we alighted the Gornergratbahn, a rack railway opened in 1898 to shepherd tourists up the steep, pine-lined slopes onto the lunar ridge of the Gornergrat. The Matterhorn dominated the view at first, thrusting like a polished canine from the great gum of rock. But as we crunched higher, watching the trees disappear around us, we found ourselves immersed in a devastating landscape. The Alps do not reveal their secrets quickly; they rise and rise, peaks layering ever steeper peaks, unthinkable pinnacles towering far above the feeble reaches of the human imagination. The higher we pulled, the more concealed spires and forgotten valleys we discovered – an alien world, as barren and foreboding as it was beautiful.

The Gornergrat complex sits upon a rocky perch overlooking the Monte Rosa massif. There is a three-star hotel, an observatory, restaurants – and an unforgettable view. The Gorner Glacier cascades in photographic freeze from a wall of mountains that, while lacking the standalone character of the Matterhorn, is more overwhelming in its enormity. The drum of a distant waterfall reverberates across the valley, granting the static glacier the illusion of torrential flow. The air is sharp and breathtakingly thin.

The view evokes that ineffable fusion of terror and awe that Edmund Burke called ‘the Sublime’. The Alps were a beacon for the Romantic poets – even now, their immensity leaves you floundering at the limits of language. But if the 19th century withheld these sights for only the most idealistic of wanderers, the 21st century Alpine experience is a less introspective, more congested affair. The path that runs from Gornergrat down to the Riffelsee, a crystalline lake stretching like a horizontal mirror before the Matterhorn’s beguiling face, is a veritable highway. While efforts are being made to minimize the damage of the enormous footfall, there can be no denying that the area has become overrun. The Matterhorn may retain its aloof majesty, and Zermatt its charming Epcot-Alpine demeanour, but the Sublime for most is no more than an Instagram filter and a few extra likes. Imagine Caspar David Friedrich’s ‘Wanderer above the Sea of Fog’ – now facing the other way, beaming manically for the selfie-stick.

The Monte Rosa hotel, where Whymper and his team first rallied, still welcomes guests. Below it lies the Whymper Stube, a subterranean restaurant serving up traditional dishes of the Valais. The lighting is low; Edward’s portrait glares unimpressed from the wooden walls. Like most restaurants around here, the stench of hot cheese cramps the nostrils, a stifling contrast to the eternal freshness of the outside. Rustic tables are wedged close together, around which harried waiters whirl, clattering down drinks with the universal strains of the understaffed. Ignoring the absurdity of boiled cheese on an already melting day, we ordered a round of the tourist staples. If Raclette is a social dish perfectly suited to a winter’s evening with friends (imagine generous scrapes of melted cheese near a crackling log fire) ours was a forlorn substitute, a miniscule side dish striped with a single dribble, a few bald potatoes and a silly pickle. Fondue, for all its woody richness, felt more like a novelty than a real meal. We lost bread to the pot, slopped cheese on the table, and committed any number of other faux pas. With a last rebellious lick of our skewers, we made an escape for the fresh air.

Because the infrastructure around Zermatt is so well developed, it requires some effort to find actual solitude. The western slopes of the Matter valley are steep and free from cable cars or cog rails, the angles naturally filtering out those who visit the area for a quick snap of the Matterhorn and an overpriced fondue. But our longing to escape the crowds meant we underestimated the challenge. A near-vertical climb propelled us off the valley floor, and soon the bustling town began to resemble a model village. We hiked through green meadows dotted with blue and yellow flowers until the altitude began to slice the vegetation away. Before long we were surrounded by colourless rock and not another living soul. All around, an eery stillness reigned.

Our plan had been to hike onto the plateau and meander south, savouring the unique perspectives of the Matterhorn, perhaps even catching a glimpse of the elusive Edelweiss. But the day was passing swiftly. We had started late and the sun had long begun her slow fall to the mountain tops. Our options were twofold: continue along the 13km path or descend the way we’d come. The rucksacks were light, the food long since gone. Ambition sent us hurtling forward. Good sense held us back.

The responsibility of being alone in nature is recognizing that you are forever at its mercy. Edward Whymper credited his years in the Alps for furnishing him with solid health and life-long friendships, but he never forgot the dangers. Trudging back to civilisation, I pondered what he would have made of modern Zermatt. The risks have been reduced; the discomforts minimized. Even the slopes can be bypassed, glided over with sedentary ease. But in circumventing hardship, we only forego any encounter with our own fragility. The pioneering spirit has long since left the Matter valley. What remains is us – the chocolate-munching rearguard.

Still, while tourism can be controlled, it cannot be stopped. There is something undeniably human about the desire to be awed by nature. The Matterhorn, that hulking behemoth of rock, will never not captivate the imagination, no matter how accessible we make it. Whymper imagined a distant day when the mountain was no more than a crumble of dust. But more likely it is we who will disappear first. Long after the wooden chalets have rotted and the chairlifts collapsed, long after flowers have grown back on the trampled paths and Zermatt is a name forgotten, the Matterhorn will remain, a dreamy testament to all that is bigger than us and our feeble machinations.

The mountains can be climbed. They can be photographed. But they can never truly be conquered. To the Matterhorn, and all like it, we are equal in our insignificance. Whymper knew that from experience. In a single day he tasted the fullest measures of triumph and tragedy, learnt the heights of wonder and the deepest troughs of despair. The darker memories haunted him for the rest of his life. As a result, Scrambles Amongst the Alps finishes with a word of warning:

“Climb if you will, but remember that courage and strength are naught without prudence, and that a momentary negligence may destroy the happiness of a lifetime. Do nothing in haste, look well to each step, and from the beginning think what may be the end.”

Sources

Edward Whymper, Scrambles Amongst the Alps in the Years 1860-69 (Project Gutenberg; 2012) https://www.gutenberg.org/cache/epub/41234/pg41234-images.html

Leave a comment